Some of my favourites this month

“A tongue-in-cheek NPR.org headline comparing the fetching abilities of cats and dogs revealed a truth known by countless cat owners: Some cats do fetch.” All right, some cats do fetch at NPR by Matthew S Schwartz.

“I’m well aware that it just takes one second for trouble to turn into tragedy. In addition, let’s face it, I tend to be on the

Some tips for how to help dogs learn to use dog doors in Help! My dog won’t use the dog door by Sylvie Martin.

“If you’re a puppy parent searching for guidance on how to socialize your puppy, you risk coming across some concerning misinformation, even from professional trainers. “ In defense of puppy socialization by Kelly Lee at the Academy for Dog Trainers.

“All he asked was that we bury you in the garden.” A letter to Ruby, my son’s sorely missed cat by Anonymous at the Guardian.

“It seems that one of the consequences of regarding pets as family members is that as kids get older, family members—including canine and feline family members—play less important roles in their lives.” Why do kids become less attached to pets as they get older? By Dr. Hal Herzog at Psychology Today.

“How do low-income households keep their pets fed when there is limited pet food in the home?” People on low incomes deserve to keep the pets they love by Linda Wilson Fuoco.

“When my therapist wasn’t able to fit me into their schedule, I turned to equine therapy” Horses, depression and me: How riding changed my life by Mari Sasano at The Walrus.

"There could be very good reasons why they don't want to interact with other dogs or various humans, and we should honor their choices and not force them to do so." Dr. Marc Bekoff asks, Do dogs hold grudges? at Psychology Today.

“I have a dog because I truly love everything about dogs.” The joy of a dog by Lori Nanan is a celebration of all things canine.

In this podcast, the Thought Project talks to Julie Hecht about dog urine, that “guilty” look, and Fear Free vets.

And the Smithsonian archives show famous people with their cats, by Jacqui Palumbo at Artsy.

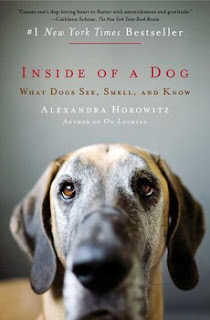

Animal Book Club

This month the Animal Book Club is reading What the Dog Knows: Scent, Science, and the Amazing Ways Dogs Perceive the World

"A firsthand exploration of the fascinating world of “working dogs”—who seek out missing persons, sniff for explosives in war zones, and locate long-dead remains..."

It’s fascinating. Are you reading it too? You can find a list of all the books and purchase via my Amazon store: https://www.amazon.com/shop/animalbookclub (I earn a small fee, at no cost to you, from qualifying purchases).

If you’re more into general chit-chat without the commitment to reading a book most months, you can always consider the Animal Books Facebook group.

Upcoming Webinar

I’m delighted to say that I will be presenting a webinar entitled Debunk, support science, or tell a story? How to communicate about dog training and animal welfare for the Pet Professional Guild. If you liked my recent post on reasons to be positive, you will enjoy this webinar.

The webinar will be on Tuesday, 16th July at 11am Pacific/2pm Easter/7pm British Summer Time.

Anyone who signs up in advance will automatically receive a recording after the event. The webinar is open to the public as well as to Pet Professional Guild members.

Support Companion Animal Psychology

Companion Animal Psychology is open to everyone and supported by animal lovers like you.

If you love Companion Animal Psychology, you can support me on Ko-fi. Ko-fi does not charge fees, and you can make either a one-time or monthly donation.

This month, I’d like to say a special thank you to Jill Bradshaw, Lorena Patti, and Rose B. Your support means the world.

Here at Companion Animal Psychology

Companion Animal Psychology has a brand new look! You should find it easier to read and faster to download. Let me know what you think of the new design. If you miss the sidebar, click the hamburger icon in the top left to see it.

Recently I was honoured to be included in LadyBossBlogger’s list of 240 badass female bloggers of 2019.

This month I was quoted in an article about the responsible pet owner’s checklist for taking care of a pet, and a review of the best dog toys of 2019.

This month also sees the launch of the new magazine, Happy Paws, from Fear Free, and I’m thrilled to be quoted in an article in the first issue about understanding the canine mind.

|

| My cat Melina checking out the new Happy Paws magazine. |

Over at my Psychology Today blog Fellow Creatures, I wrote about how to find a missing cat (including some tips to help prevent them going missing in the first place). If you're ever in the unfortunate position of having a lost cat, I hope these tips help (the most important thing is to look very carefully very close to home). I also wrote about how a viral video affected the perception of lemurs.

One of my favourite posts of the last month is animal lovers on the books that changed their lives. I found it inspiring to learn about the books that have made a difference to people, and many people have told me they feel the same. So I will be putting together another version of this post. If you would like to contribute, email me on companimalpsych at gmail dot com and tell me which animal book changed your life, and why. Include your website if you would like a link back. I look forward to hearing about the books that are important to you!

This month I also looked at which dog breeds are the best alternative to the French Bulldog for people who are concerned about the welfare of this breed. Thank you to everyone who shared their suggestions with me.

I wrote about some research that shows smaller dogs live longer than bigger dogs – and just how much by, depending on breed. As well, I covered an important new review paper that investigates how we can make vet visits less stressful for dogs; the article contains lots of tips and a temporary link to download the paper for free.

Reasons to be positive about being positive in dog training looked at the lessons we can draw from research in psychology and communication. If you’ve ever wondered about the best ways to debunk an idea, or if you should focus on other messages instead, this article is for you (as is my upcoming webinar at the Pet Professional Guild).

At the end of last month, Companion Animal Psychology turned seven years old. It’s hard to believe I’ve been blogging this long and written so many words about science and our pets. As I said in that post, I'm very grateful to all of you for your support and encouragement.

Pets in Art

This month’s pets in art shows an old woman with a cat by German artist Max Liebermann, from the Getty collection (open access).

I love the way the woman and cat are looking at each other. As well, I have to admire her skirt and apron.

Here are the catalogue details:

Max Liebermann (German, 1847 - 1935). An Old Woman with Cat, 1878, Oil on canvas.Here are the catalogue details:

96.5 × 74.9 cm (38 × 29 1/2 in.), 87.PA.6. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. As an Etsy affiliate, I earn from qualifying Etsy purchases.